With recent new releases, including Marie Kreutzer’s Corsage and Noah Baumbach’s White Noise, dancing their way through the end credits, Fabian Broeker explores the relationship between music, movement and a film’s final moments.

In cinema, ending credits give the audience room to breathe and a space to reflect upon that which they have just seen. A moment of limbo in the auditorium before the lights turn on.

Occasionally, a director foregoes this unspoken agreement between film and audience. Claire Denis’ BIFA-nominated Beau Travail (1999) is perhaps the most striking example of this subversion, transforming its credits into a dance sequence which not only continues the film’s narrative, but in many ways transcends it.

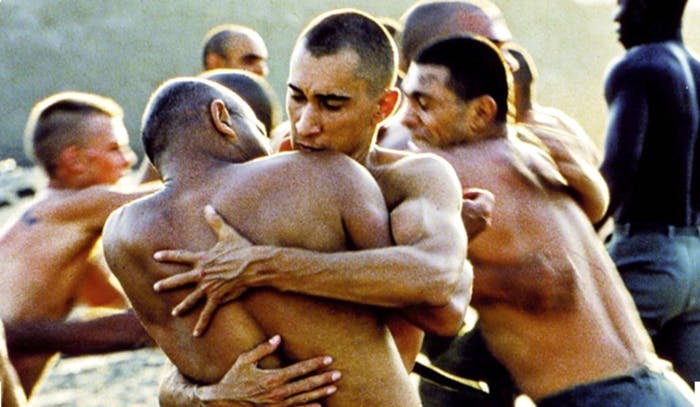

Beau Travail, an amalgamation of Herman Melville’s Billy Budd and Benjamin Britten’s opera of the same name, explores masculinity and otherness via the relationship between three soldiers. Set within a Foreign Legion regiment in Djibouti, the film focuses on the dynamic between Sergeant Galoup (Denis Lavant), his commanding officer Forestier (Michel Subor) and new arrival Sentain (Grégoire Colin). Against the backdrop of balletically choreographed military drills, the film explores the ambiguous relationship between Galoup and Sentain, with the tightly-wound, reptilian Galoup, becoming increasingly fascinated and jealous of the young, heroic, beautiful Sentain.

Galoup eventually sends Sentain out into the desert with a faulty compass in a ploy to kill him, and is exiled from the regiment as punishment, returning to France. In the final moments of the narrative, Galoup, who remains an impenetrable psyche at the centre of the film, an empty shell of a man, methodical and plain, neatly makes his bed, before lying on it holding his pistol.

Yet, while the credits flash on the screen, the film suddenly places Galoup alone in a mirrored room housed within what is presumably the Djibouti disco previously glimpsed in the narrative. He begins to move slowly as the universally recognisable dance hit, “The Rhythm of the Night” begins to play, before increasing his swaying into an almost manic, explosion of dance.

Why, when, and how this sequence fits into the narrative remains unclear; instead, Denis almost breaks the fourth wall. The repressed, opaque emotionality of Galoup is shattered in these final moments. It is as if Denis frees her character, or rather unleashes him from the shackles of a life lived constrained to conform to ideals of masculinity and regimental militarism. Perhaps Galoup has left the world of the film altogether, gliding through the credits, a body no longer moulded by the military drills of the film, but set free to dance for the audience. In this way, the audience feels almost uncomfortably close to Galoup; it is no longer a relationship anchored via the film’s script, but one based purely on a kinetic energy, trapping us here with an uncanny visual spectacle as the credits roll.

This kind of drastic transformation of cinematic closing credits, turning contemplation into celebration and allowing characters to transcend the cinematic narrative, has recently re-emerged both in Noah Baumbach’s White Noise (2022) and Marie Kreutzer’s Corsage (2022). Indeed, these film’s act as worthy successors to Beau Travail’s climax.

Corsage, which mixes fact and fiction in its portrait of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, uses the closing credits to give its heroine a reprieve from the toils she has faced throughout the film. In an extended, high-energy dance sequence, Vicky Krieps’ Elizabeth twirls through the frame. The chaos of her world, which pushes her to attempt to take her own life on multiple occasions, is lifted in these final moments, transformed into dance and a celebration of this character.

Baumbach’s White Noise, an adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel of the same name, a narrative with the fear of death at its thematic core, turns its credits into a spectacular, large-scale dance sequence inside a supermarket. Baumbach casts this final scene as “a dance of life, which is also a dance of death”. The film up to this point is very much beholden to the novel, yet here elevates the film from the written word, utilising a form impossible to replicate in literature. In its final moments, the film moves away from DeLillo’s text, and seeks to distinctly, and irrefutably mark its own existence as a work of art.

Interestingly, for Beau Travail’s final dance, Denis’ only instruction to Lavant was to “perform the dance between life and death”, uncannily similar to Baumbach’s vision, albeit on a far grander scale, decades later. It is perhaps the form of dance, the act of communicating through bodies, without words, simply by manipulating space, which makes it such an appealing tool in explorations of life, death, and the moments in between, and which makes it arguably the perfect medium to fill the limbo between the credits rolling and the lights in the auditorium reluctantly flickering on.